|

| Fragment of buckle frame found in our unit |

While doing archaeology, you never know what secrets the

ground might hold. For instance, yesterday, while excavating our unit, my unit

partner and I uncovered what appeared to be a rusty nail. When we are digging

in the layers believed to be undisturbed, we pedestal around artifacts to leave

them in situ until we map the unit. While

mapping, we noticed that what appeared to be a rusty, slightly bent nail was something

much more. The clinging dirt and small bits of corrosion were removed and an

ornate fragment of some variety of buckle. The decoration includes a small

heart motif with a "wrapped wire" molded design.

Now,

not knowing much about buckles, especially those from the 18th century and not

the belt variety from the 1980s with unicorns on them, I decided to do some

research. However, now I know more about them than I have ever dreamed, mainly

because I've never dreamed about knowing about buckles.

Most

people consider buckles' only use to be to secure belts. But, between the 17th

and 18th centuries, buckles had diverse roles. In addition to belts, buckles

were used on shoes, breeches, harnesses, stocks (a men's garment that consisted

of a piece of cloth wrapped around the neck and secured with a tie, or you

guessed it, a buckle), girdles (a women's fancy belt worn with fancy dresses),

hats, and with long boots (garter buckles), swords and spurs. They also had

varying levels of decoration, frequently based on function but also

socio-economic status. For instance, garter buckles are generally undecorated,

while girdle buckles tend to be the fanciest. Shoe buckles, however, can be a

simple rectangular frame, or a valuable, highly decorated gilded piece with

intricate scrollwork. Shoe buckles are often an indicator of socio-economic

status because of the high variation of ornamentation, though the presence or

lack of an elaborate specimen alone cannot be the sole deciding factor.

.jpg) |

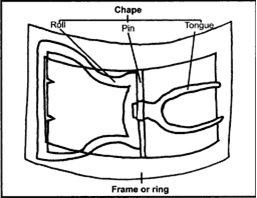

| Anatomy of a buckle (Image from White, 2005) |

In

addition to function, buckles can vary greatly in material, from copper alloy,

to iron, pewter, and gilded or plated metals. They may also have inlays, such

as shell, ceramic, wood, precious or semi-precious stones, or "paste"

stones. Paste stones are false gemstones, similar to rhinestones, made out of

flint glass and high in lead content, and are often preferred for use in shoe

buckles, due to inexpensive pricing as well as ease of setting into the buckle.

Buckles

can also be used diagnostically for dating purposes, especially shoe buckles.

They generally were only in use between the late 1600s until the late 1700s and

early 1800s. Also, styles changed greatly in that time as well, with larger,

more ornamented shoe buckles being later than smaller, simpler ones. Decoration

can also play an important role in dating a specimen.

Diagnostically, certain

aspects of a buckle can be used to determine its function. Size and decoration

are important, but also aspects such as frame and chape (the interior part of a

buckle, see diagram) design are key elements to consider. For instance, the

frame of a shoe buckle will be more curved to fit the contours of the foot,

whereas a knee buckle, used to keep breeches tightly fitted to above or below

the knee, will be more flat. And, more visible buckles tend to be more highly

decorated, at least if socio-economic status allows for it-- so shoe, knee,

hat, and stock buckles are often those most highly ornate.

Our

fragment of a buckle frame seems to be from a shoe, based on its curvature as

well as size. While the fragment is only about 40mm long, it appears to have

had a height of around 45mm. The width is difficult to project, as not enough

of the fragment remains. From colour, patina, and weight, it seems to be made

of pewter, though closer analysis should be made. Interestingly, a nearly

identical fragment was found at Fort Michilimackinac, and was made of brass.

It's about the same length, except it broke off at a slightly higher point, and

bears the same decoration. The heart motif was important in Jesuit designs,

which could imply origins of this buckle.

In

summary, something as mundane as a fragment of a shoe buckle can tell us a lot

about not only the particular area in which it was excavated, but also about

how people lived at Fort St. Joseph. Even at a post in the wilds of Michigan,

ornamentation and personal decoration seem to have still been important in everyday

life.

.jpg) |

| Fragment of buckle frame found at Fort Michilimackinac (Image from Stone, 1974) |

Sources: Kerr, Ian B.

(2012), "An Analysis of Personal Adornment at Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), An

Eighteenth-Century French Trading Post in Southwest Michigan". Master's

Thesis. Western Michigan University, Department of Anthropology.

Stone, Lyle M.,

(1974). Fort Michilimackinac 1715-1781:

An Archaeological Perspective on the Revolutionary Frontier. Publications

of the Museum, Michigan State University

White, Carolyn L.,

(2005). American Artifacts of Personal

Adornment 1680-1820: A Guide to Identification and Interpretation. Altamira

Press.